On National Caregivers Day, Thanking the Colleagues Who Helped Me Care

On a hectic morning in the California Attorney General’s Office, I’m juggling a notebook, coffee, and two phones—one of which just went off for the eleventh time in a row. Discreetly checking the buzzing in my blazer pocket, I see the name on the screen: “Dad.” Again. I’m 3,000 miles away, with no way of knowing whether it is a real emergency or a feature of this stage of dementia. Either way, I’m praying it can wait until the end of this meeting.

It’s a familiar scene for anyone who has cared for a loved one with dementia, the 12 million Americans I’m thinking about today. A year passed since my final “shift” on my dad’s care team, I’m beyond grateful for our final chapter together—and the supportive workplaces that made it possible.

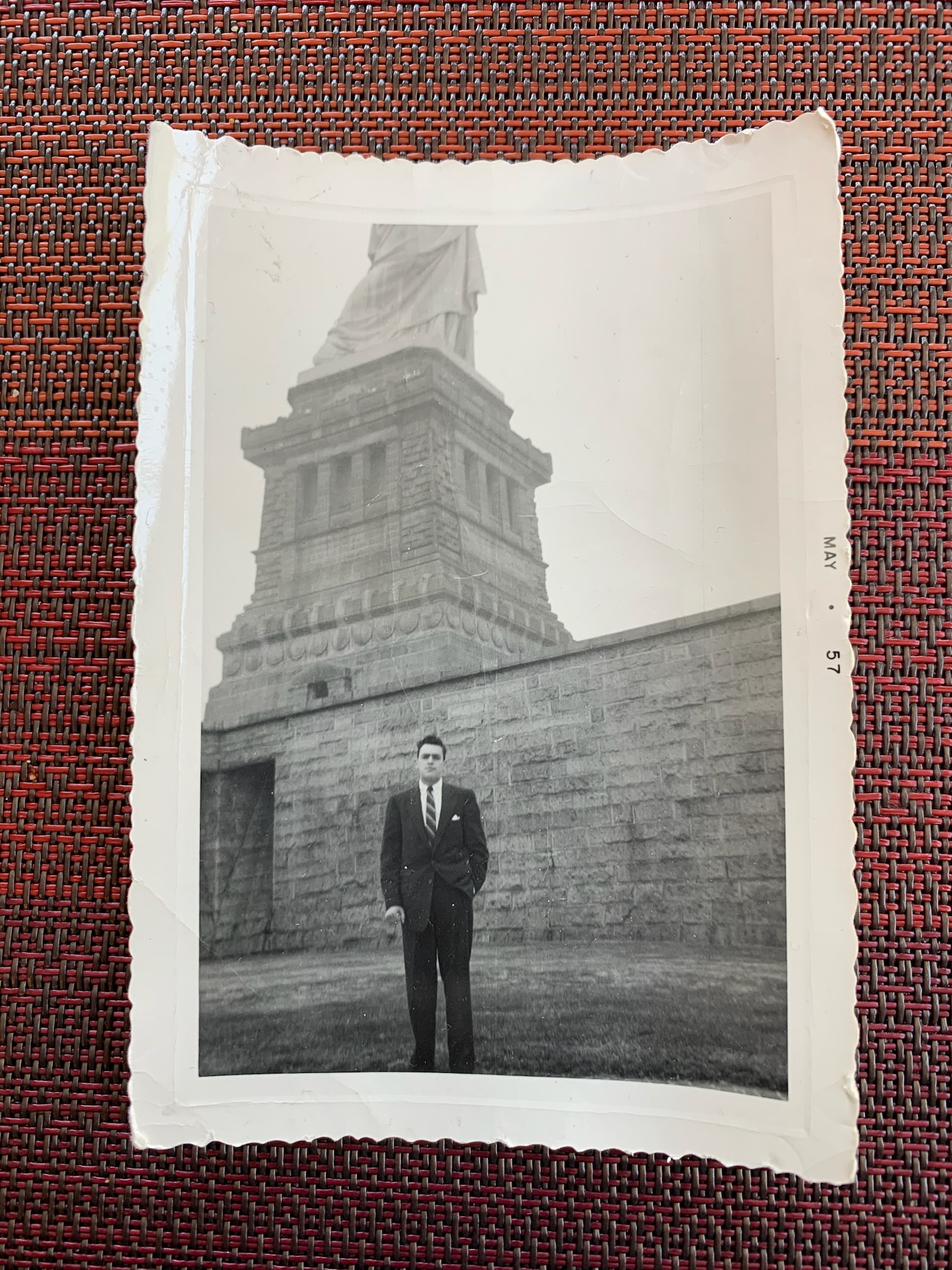

That I ended up in a politician’s office that morning was no accident. My dad, Guillermo “Bill” Moscoso, an Ecuadorian immigrant, loved politics. By the time I was born—his surprise, later-in-life baby—he had been a proud American citizen living in the Washington, DC area for more than two decades. PBS NewsHour was our nightly dinner companion, and Meet the Press joined us for Sunday brunch. My dad would talk to me about the news, asking for—and valuing—my nascent opinions. When I developed my own passion for public service, he encouraged me endlessly. He drove me downtown for summer internships and even got to meet President Obama while I served in the White House.

But short-term political appointments don’t mean much job security, and in 2017, it was time for a new opportunity. When I got a chance to continue as a public servant and speechwriter in California, my dad encouraged me, even though it meant a cross-country move. My caregiving journey got off to an unusual start, in my 20s, and on the opposite coast from my loved one. My mom led our caregiving team, and I helped from a distance—scheduling doctors’ appointments, calling pharmacies, and traveling home whenever possible.

Soon enough, I was living the lines I had written in speeches over and over:

“No one should have to choose between the job they need and the family they love.”

“States like California are leading the way on paid family leave.”

“You shouldn’t have to win the boss lottery to be able to care for your loved ones.”

They all took on a new meaning from my desk in Sacramento, balancing two phones and two sacred responsibilities.

Luckily for me, I did win the boss's lottery—twice. My boss Bethany, who sat with me in the Attorney General’s office that morning, encouraged me to work from the DC office around trips to see my family. That way, I wouldn’t have to use (much) vacation leave to help with caregiving. Bethany trusted me to be responsive and work hard wherever I was, years before the pandemic had proven the viability of remote work. That I left that role with any sanity, or remaining vacation days is thanks to her.

Later, at the writing and executive communications firm Fenway Strategies, I found pretty much everything I needed to grow as a writer and a caregiver. As fellow speechwriters, our managers truly understood and fought to protect the unstructured time that makes for good writing. I soon learned it also makes for a good life: With so much autonomy, I could schedule hospice calls and caregiving around my work responsibilities; no questions asked. A part of a small and relatively young team, too, I was the first to use bereavement leave—and got all the time and space I needed to grieve after my dad died.

Bethany and Fenway didn’t support me because the HR handbook or labor law said they had to. (Though it should!) They chose to be supportive—and human. They chose to trust that I could do my job and care for my dad. They chose to build a team where everyone can show up as their full selves and do great work together.

I think their choice was a good investment, too.

It made me a better writer. It deepened my connection to the one in four adults in the United States who are caring for someone. Caregivers come from all walks of life, economic backgrounds, and political ideologies. This shared experience of caring for a loved one has helped establish common ground with people who are different from me—truly, I believe, the highest purpose of speechwriting.

My bosses’ support also made me a better colleague. I felt (and feel) a deep debt of gratitude to everyone who took on extra work during the acute moments of caregiving. After the sleepless nights that came with my dad’s insomnia, or the sundowning that could sometimes be heard on Zoom, no matter how quickly I hit “mute,” I was treated only with sympathy and concern. So today, if a colleague has to take their child to the doctor, covering a meeting feels like the least I can do. I will gladly contribute to our team culture of support and understanding.

Above all, caregiving in these jobs helped me not only care for my father’s health, but also his dreams. The career I got to establish—and keep—in public service was more than he could have imagined when he came to America. Thanks to these leaders, I never had to take my foot off the gas on my ambitions to build a better, fairer country. He couldn’t communicate much in his final years, but holding his hand on the couch or hospital bed, I know that he was still so proud of the work I was doing—and just as grateful that I could keep doing it.

It might take years for lawmakers to advance policies that afford other caregivers the hard but beautiful final years that my dad and I shared. It might not happen in our lifetimes. But we can all decide how we treat our colleagues who have caregiving responsibilities. We can choose to show up for our teammates with compassion and understanding. Because if we’re lucky enough to love someone as much as my dad and I loved each other, we’ll want to care for them someday.

We should all work in places that let us.

.png)

.png)

.png)